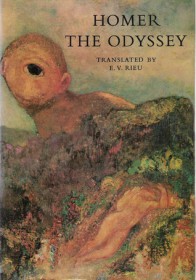

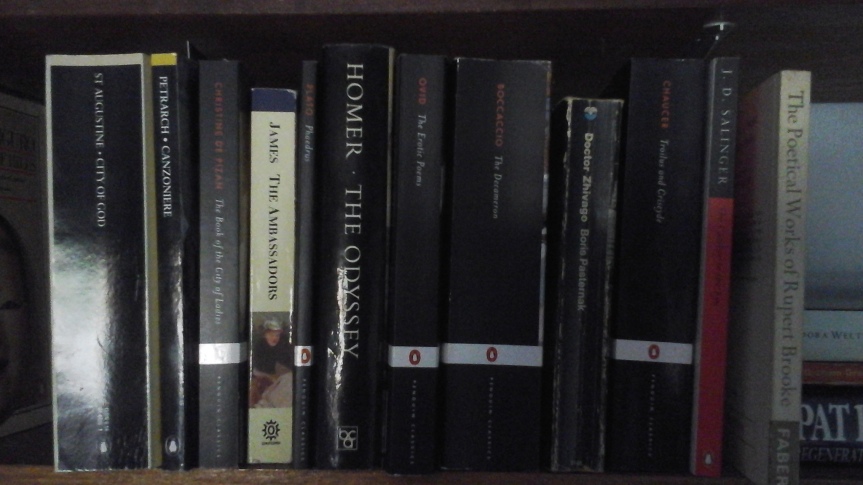

The Odyssey is a bit of a romp. It’s much more of a ‘Boys’ Own’ adventure than I was expecting and it’s for this reason that I finished it sooner than expected. Although it’s poetry, E. V. Rieu chose to translate it as prose and that makes all the difference. I’ve tried to read the other great post-Trojan War classic, The Aeneid, and had to give up when the refugees started holding boat races, which were described in minute detail.

This may reflect the differences between how stories were told in eighth century BC Greece and how they were told in first century BC Rome. On the other hand, it might just reflect the fact that I had to read bits of The Aeneid at school, in Latin, and didn’t get on with it.

The Odyssey is not a poem that could have been recited in its entirety over one evening. It requires a greater investment in time than that. Odysseus, the hero, doesn’t even appear until the fifth chapter. The reader is first introduced to his nineteen or twenty-year-old son, Telemachus. Telemachus is a puzzle to me. He’s a grown man, he’s brave and he’s Odysseus’ son, but he hasn’t taken charge of his father’s house in his father’s absence. He allows a group of men to court his mother, whilst they invade the house every day and eat his (or his father’s, since Telemachus believes that he’s still alive) goats, sheep and pigs. Things are so bad that they try to kill him. I don’t understand why he and his servants don’t see them off. If Penelope, his mother, is a widow, surely he has inherited his father’s property. I know it’s a less interesting story if Odysseus doesn’t have to rescue his wife, but it means that we spend 60 pages in the company of a young man who’s a bit of a failure.

When Odysseus does appear there are storms at sea, shipwrecks, encounters with seductive goddesses, and cunning tricks. It’s all terribly exciting, even though all his companions die on the way home. Suffice it to say that none of them dies quietly in his bed. Whilst Penelope has been fending off potential suitors since the fall of Troy, Odysseus has been the lover of goddesses and mortals. Double standards applied even then.

It all ends in a bloodbath, of course. Odysseus, Telemachus, a swineherd and a cowherd take on Penelope’s suitors. It was during this battle that I realised why Telemachus hadn’t been able to do anything about the suitor. There are lots of them and they have the support of many of the servants. There’s a particularly nasty scene where most of the maidservants are killed because they were the suitors’ lovers. Their deaths seem even worse because they’re first made to clean up after the battle in which their lovers were killed.

There’s a rather odd visit to Hades with the suitors, which demonstrates that the even the dead don’t see things as they really are.

There are some dull bits and a surprisingly large number of repetitions, but the whole thing mostly moves at a great pace. The Odyssey is the best part of three thousand years old, but it’s still extremely entertaining.

April Munday is the author of the Soldiers of Fortune and Regency Spies series of novels, as well as standalone novels set in the fourteenth century.

Available now: